Eve carved in stone and created as a lintel as opposed to Eve made from the rib of Adam-She is a 12th century pin up, more sensual and provocative than any Eve in the lexicon of temptresses from Cranach to Bacon. She reaches back with her left hand for her chosen fruit while she puts her right hand to her lips. Why? Is she swallowing her last bite of innocence or is she anticipating, with that slight smile, the task before her. She lies on her side whispering through her hand to a now absent Adam, similarly reclining and long since lost. (The two, no doubt, were an echo of some surviving classical model. The Eve had disappeared after having been carted down to the foot of the hill where the stone on which she is carved was used as building material for a house constructed in 1769. She was discovered when the building was torn down a century later and is now the prize exhibit of the Musée Rolin. The Adam she is tempting has never been found.) She slithers like her benefactor, who is close behind with his great forked tongue blending into the foliage that surrounds her. Unaware of her nudity, we are shielded from a view of the womb of all mankind by a magnificent pomegranate.

The most prominent pomegranate myth is associated with pre-Christian Persephone. She is tricked by Hades, the god of the underworld, into eating pomegranate seeds, thus binding her to spend a portion of each year in the underworld. The symbols are not lost. The cycle of seasons and the transition between life and death pre-figure our lovely Adam and Eve; This myth, often, represents the pomegranate as a symbol of both fertility and the underworld due to its connection to Hades. The jewel fruit has no equal. What apple? How did artists through the ages miss this opportunity? My husband just handed me a pomegranate as an anniversary gift, a jewel of fruit for the month of December.

Who, pray, could carve such a sultry creature of desire? ...a man who left his name, knowing full well that he had given the world of the 12th century something exquisite...His name was Giselbertus. It is 1135, a full 230 years before one point perspective makes its way into the Italian Renaissance.

What do those words mean in 1130? What does the world look like in 11803? Even more, what was it like to live in a thriving, pilgrimage town in France, under the weight of pictorial judgement in stone?

We visited the exterior only this time. It was near dusk. It was more profound then ever before because it may be the last time. Perhaps, we had come to say, Good-bye to Giselbertus, on this side, at any rate.

The iconography of Romanesque architectural sculpture is almost universally closely related to its (original) location on the building. At Saint Lazare in Autun, the placement of the Last Judgement tympanum (c.1125) over the portal of the west façade might appear to address those entering the church, reminding them of the reckoning to come at the end of days. Was Giselbertus referring to his public or to himself? His work is so intimate, so full of passionate narrative, it is impossible to separate the man from the artist.

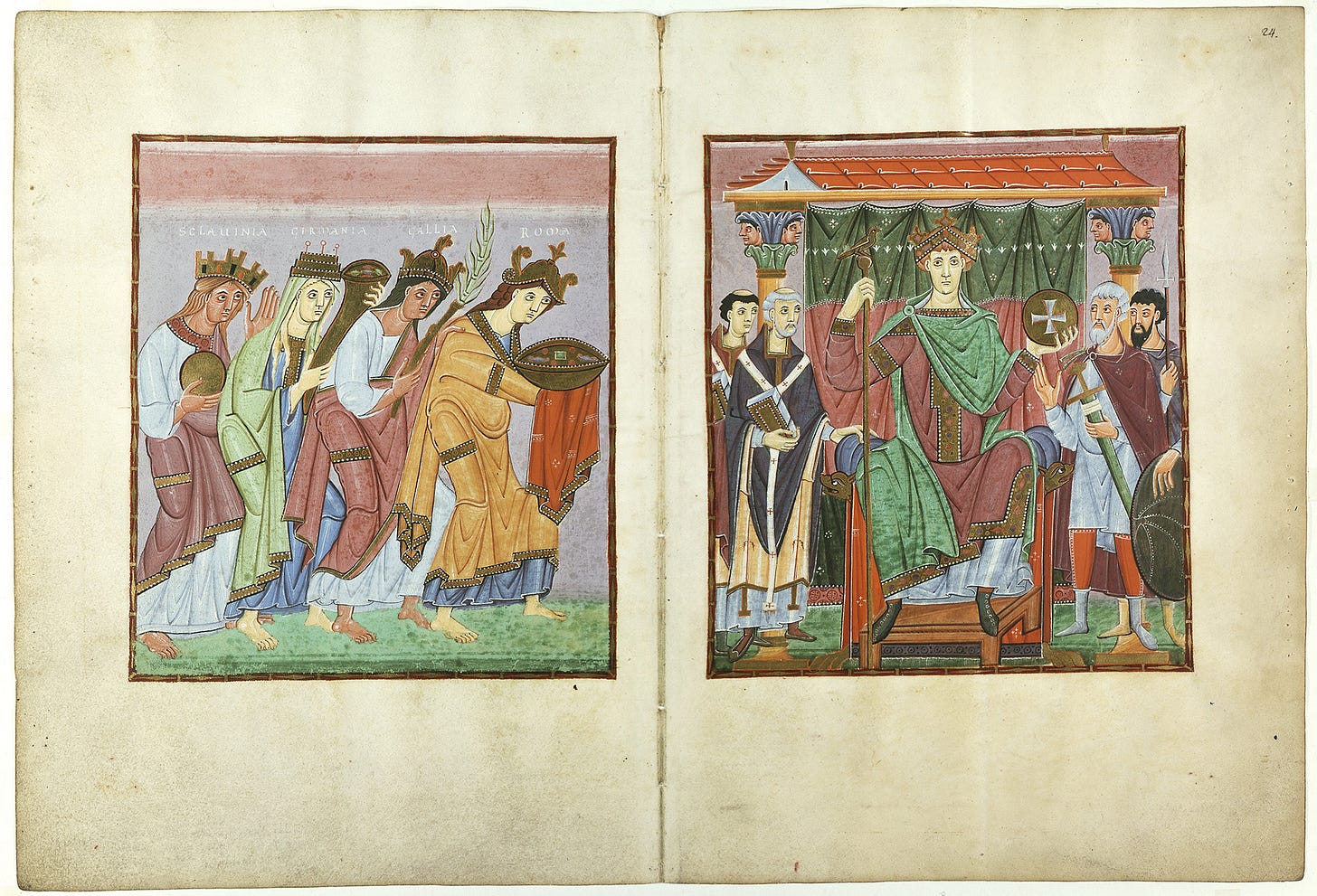

His signature, written at the feet of Christ, speaks of a man of will, working in a time when an artist was nothing more than a tool. Little is known of him. His signature is accompanied by the bishop's seal so he was "somebody." Christ in mandorla, encased in the almond shape, a recurring theme of 12th century art, Gislebertus offers up an unparalleled monumental work of the unfolding drama. All of this energy of people moving from the grave to heaven or hell sits on the head of Lazarus. (third photo) The figures that create a lintel below are naked in every possible pose, waiting for their final assignment. This is 1125, 125 years after the reign of Charlemagne's descendant, Otto III.

If you click on the photo above, you can see more clearly, the calm figure of Lazarus, sculpted in the tympanum as he holds up the the entire Christian ethos of death and resurrection. But, is he the real central figure? Sure...in the 12th century, I am sure that the un-discerning, overwhelmed, exhausted, footsore pilgrim on his way to St Jacques d' Compestello may not have noticed the girls that flank Lazarus. Mary and Martha, the sisters of Lazarus, the key players in the story, who asked Christ to raise Lazarus, their beloved brother, from the dead. It is a double score for the pilgrim. If the message was not clear after standing under this monumental masterpiece, they might as well turn back. But if the pilgrim caught the essence of the entire story of temptation, exile and redemption, then, walking the next 915 miles would be a proverbial piece of cake. These great Tympanums of Autun, Vezelay, Conques, Mossiac were sign boards of inspiration that put their towns on the map of the journey insuring tremendous tourist trade but also, offering a spiritual push to get on with it and complete the journey to Spain and earn that scallop shell, the most recognizable symbol of the Camino de Santiago.

It represents the pilgrim’s journey from all corners of the world and converging at the tomb of Saint James in Santiago de Compostela. The scallop shell is also a symbol of rebirth, a metaphorical representation of leaving the old life behind and embarking on a new spiritual journey. The shell’s ridges and grooves symbolize the different routes of the Camino de Santiago and the detours and hardships that pilgrims may encounter as part of their journey. The use of the scallop shell in the architecture of churches, monuments, and hostels along the Camino further reinforces the importance and meaning of the symbol for pilgrims. It serves as a reminder of the spiritual journey and its ultimate destination. How utterly irresistible! No wonder Chaucer's Wife of Bath made all three pilgrimages, Canterbury, Santiago de Compostela and, finally, Jerusalem. Who would want to miss it! Think who you could meet!

The history of Autun as a venerable pilgrimage city has roots going back to Roman and Celtic Gaul. St. Lazare, as a church with the history of the tympanum is not mentioned in writing until 1482. The reader can really only suppose and interpret through the sculpture itself. How has this place escaped a novel or four or a film with the tortured Giselbertus, in mad love with the model for his Eve, who might have been promised to the local baker and just out of his reach. Alas, nothing is known of him except the name he left us.

Michael weighs the souls to the right of Christ while Satan captures and desposes the souls of the unredeemed. My, what a way to keep a society in order...at least on the surface.

Eve eyes are deep set with heavy eyelids, bulging eyeballs, deeply drilled pupils, with sharp lower ridges. A faint mark appears in the inner corner of her left eye and suggests the possibility of a tear forming there. Perhaps, because in the 18th century, she was dismantled from the North Portal, considered to be a bit licentious for a exit archway. She lives in the museum in fragments which is good enough for us to get the drift of her intentions. The lyricism is not lost. It is palpable.

The stories of Lazarus and Adam and Eve are juxtaposed. Lazarus, as an allegory of confession and Adam and Eve, as an allegory of non-confession. Werckmeister concludes that Eve's depiction in the lintel relief is a connection of two narrative moments: the top half of her body, which regrets her sin, and the bottom half of her body, which is about to commit the sin...Freud could have feasted on this supposition to say nothing of the common day expression of thinking with one's body parts.

Gislebertus Eve is depicted in a style typical for Eve in Romanesque sculpture is because this particular Eve is intended to be emblematic of Eve before the FaII, not Eve after the Fall. This girl is thinking with her whole logic combined with desire. There is no, "What were you thinking?" This Eve knows exactly what she is doing. The age of reason is born. Apollo and Bacchus meet at the gate, as it were. Eve can be seen as locked in the moment of decision, choosing between virtue and sin. If you look closely, the decision has been made.

To the Burgundian mind, Mary Magdalen was linked with Lazarus. as she was perceived to have been his sister and to have come to France to proselytize with him. The 12th century pilgrim, having traveled from afar thought it was completely plausible that the biblical Lazarus with sisters, Mary and Martha, came to France, thus the relics of St. Lazare or Lazarus are on the altar. The relics are from as early bishop. This is doable. Was Mary, the sister of Lazarus the same Magdelan-combining the Biblical bad girls in one sculptural package? clever, delightful, even humorous but unlikely....delicious...but no. However, for the pilgrim who had the time and inclination the discussion of grace and free could be inspired by the iconography of this stonework all day long.

The question that I find rather haunting is this, could Giselbertus read or was he told the stories by a very well-read monk? His capitol sculptures refer to Daniel, Ezekial, even Revelations in such profound interpretation that he would have seemed to be a scholar on some levels.

"Work on the church began about 1120 when Autun was a part of Burgundy. Originally intended for lepers, it was dedicated to St. Lazarus and his relics Also, it was intended that the church at Autun should be an imitation of the one at Cluny, but the vault of the nave at Cluny Abbey collapsed after five years and the plans for Autun underwent some radical changes. Gislebertus then became the new sculptor with a contract that was to occupy him for at least the next ten years.

Nothing is known about Gislebertus as a person and questions nag any discussion of him. He lived in Burgundy, but it is not known if he was born there. He is believed to have worked at Autun from 1125 to 1135. Since there were no art or architectural schools at that time he may have received his early training as an apprentice in one of the rock quarries that were then the focal points of the building trade—starting on simple figures and low-relief foliage and progressing to deep carving. His apprenticeship over, he is believed to have worked on the decoration of the Benedictine abbey of Cluny and, later, the Church of La Madeleine at Vezelay.

Gislebertus was probably not a monk, but as a close associate of churchmen, he most likely had a fairly thorough education. It would be interesting to know if he belonged to the guild of Mortelliers et Tailleurs de Pierre, or whether he used the quaint title of Doctor Latomorum (doctor in stone carving). Dr. Zarnecki suggests that he may have been a member of the team that created Vezelay’s great tympanum (1120–1125). If so, then his supervisor was the unnamed “Master of the Tympanum,” regarded as Cluny’s most important sculptor and an important influence. On these assumptions one can build the premise that when the Duke of Burgundy and Bishop Etienne de Bage undertook the building of a new cathedral at Autun they already had great respect for Gislebertus and engaged him to provide ornaments for its outside portals and inside piers.

When Gislebertus arrived at Autun, stone carving was no longer done in the quarry. He probably had his own shed near the construction site, with a sand bed on which to assemble and skillfully fit together the 29 blocks of the tympanum, plus assistants to prepare the blocks and carve the simpler ornamental patterns for the highest pillars. Messrs. Zarnecki and Grivot believe, however, that Gislebertus did all the figure groups himself, with the exception of two scenes attributed to his pupils.

He must have worked ceaselessly to complete so great a project. Stone carving is and always has been a time consuming art and because of this churches of the Middle Ages were generally assigned to workshops of artists, mostly unidentified as individuals. Disturbed by the rankling question of one man’s ability to do this body of work in ten years, Dr. Zarnecki discussed the problem with many stone carvers. At the St. Isidorus cloister of Leon, Spain, he met a stone carver who, without formal training and with tools surely as crude as those used by Gislebertus, could turn out a high relief capital in a week. Hence Gislebertus could have done it. And it just could be that this unrelenting pace accounts for the expressive spontaneity that marks his work.

Gislebertus had completed his work by 1135. Where he went from Autun is not known. The cathedral itself was not finished until a decade later, when it was both praised and criticized. A veritable Bible of stone, it contained more than four hundred figures, eighty-six of them in the tympanum alone—a vast theological panorama of the Last Judgment depicting Christ as the central figure, with palms out and knees spread in a gesture of compassion and beneath whose feet Gislebertus inscribed his famous signature. "In the total church carving, Jesus is portrayed sixteen times, Peter six times, Judas once (hanging by the neck), thirty angels are busy on a variety of missions and eighteen devils are likewise busy on countermissions." There are sixty leading characters of the Old and New Testaments and thirty lesser personages.

Add to these seventy animals both domestic and wild and twelve monsters serving Satan, and even seen through the eye of the camera this adds up to a massive amount of carving. For Gislebertus to be given so much space for a self-glorifying signature in so prominent a place indicates that the clergy of Autun thought highly of him indeed. But not so one of their contemporaries, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote in part (1125): “The Church inlays the stones of cathedrals with gold but leaves her sons naked. . . . Why, in an age when so many of our brothers can read, such ridiculous monsters, such abhorrent deformities? What are they doing here—these revolting apes, ferocious lions, centaurs, spotted tigers, and horn-blowing hunters . . . everywhere a variety of shapes so astonishing that the worshiper finds it more entertaining to read the stones than books. Great God! Even if no sense of shame surges at the sight of such futility, why not at least deplore the high cost of it all.” Ah, well, there is constant state of change. We see this in our daily lives and Bernard was nothing is not reactionary.

The following is the most charming story of discovering the head of Christ in Majesty...

"Abbe Grivot, choirmaster of St. Lazare and a student of Romanesque architecture. One November afternoon in 1948 he borrowed a random head set to the side of the cathedral, climbed a shaky ladder to the top of the tympanum, lifted the 40-pound stone to the top of the headless figure and found that it fitted perfectly. It was indeed the missing head of Christ in Majesty. Thus began the investigation which, lasting eleven years, encompassed a study of the figures on piers, niches and tympanum, many of them beyond the line of everyday sight and some long since fragmented or dispersed." It is assumed that the destruction was the work of the Revolution.

Of all the mysteries surrounding the sculptor and sculptures of St. Lazare, one of the greatest is: why, with so much evidence before them, succeeding generations of scholars, even after restorations were made, gave so little heed to the hypothesis that a single artist might have conceived almost all of the statuary, both inside and out." Gibelbertus is our tortured Michelangelo of the 12th century. He is very simply unequaled. A Master, like Leonardo, of human interest with the capacity to interpret the human condition. He is no less important that either of the above. Perhaps, in his solitary gesture, he is even more important.

Thus, I give you Autun and Giselbertus as a gift for the season.

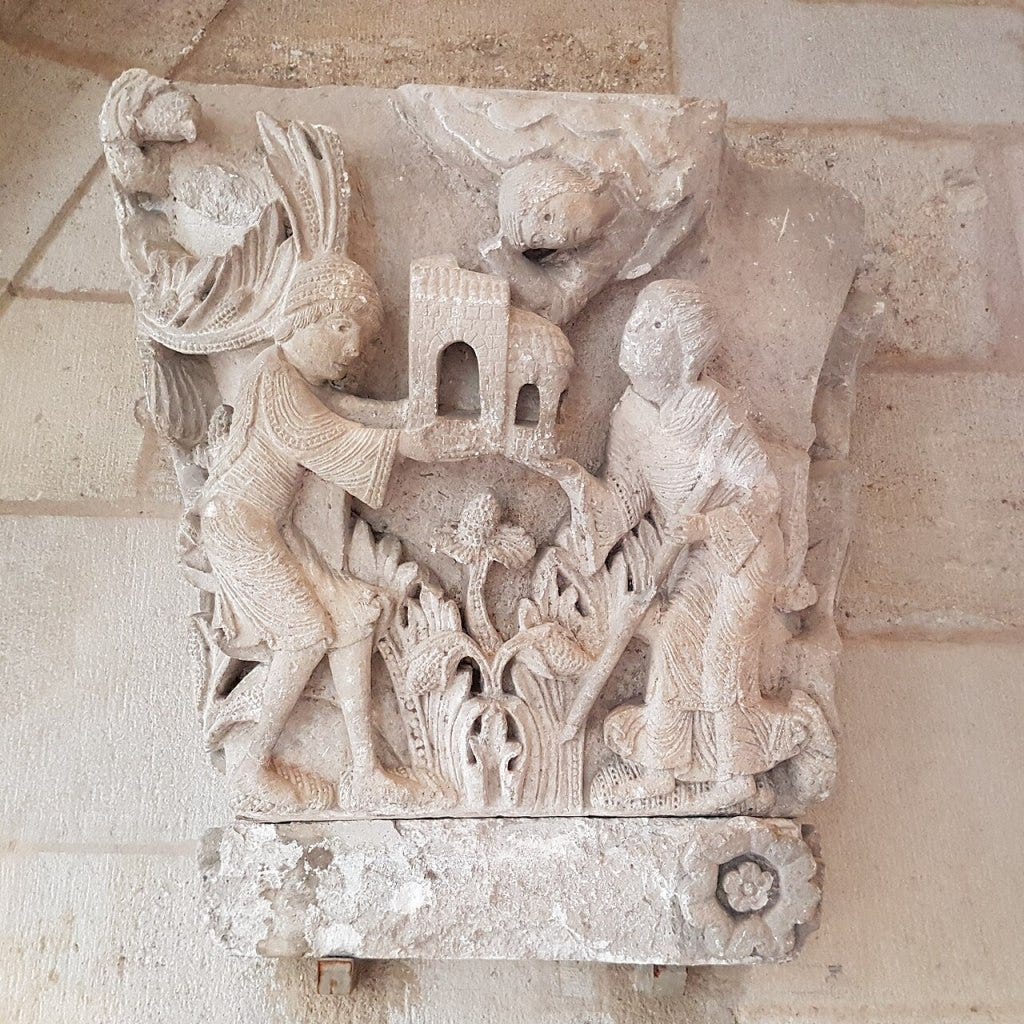

Detail of the carving from the cathedral of St Lazare in Autun, France. This scene shows the Adoration of the Magi (The three kings bringing gifts to the newly-born Jesus). (For more information about the building see Paradox Place).

this was enthralling Thank you, Mary, for bringing it all together. But what is Paradox Place? My computer would not link to it.