Woman and Child in the Garden, Berthe Morisot, 1884, Scottish National Gallery (On Display) depicting Julie Morisot

This winter was not for sissies. January was a whole year within a month. Shortly after the holidays, my husband and I plunged into a study of 1874 and the Dawn of Impressionism. Each February for the last three years, we offer a Zoom presentation of some aspect of art and history. Yes, I realize it is a wonder that there is not murder and mayhem in the house but somehow, after years of team teaching, we battle through what is relevant, hopefully intriguing and somewhat compelling. Everything revolved around an earlier autumn trip to Paris.

The View from Passy Bridge Henri Rousseau, 1895

We secured a charming flat in Passy, an outlier arrondissement away from the main stream of the usual Left Bank locations. This was simply a bit of good luck. We had dropped ourselves just off of the Rue Franklin, within walking distance of one of the former homes of Georg Clemenceau , the controversial Prime Minister of France and great friend of Claude Monet, and down the street from the childhood home of the artist, Berthe Morisot and a stone's throw from the parental home of Edouard Manet, the trailblazer of Modern Art...isn' tthat the most divine run on sentence! An added bonus, there is wonderful cemetery at the bottom of the hill. The Cimetière de Passy, located at 2, rue du Commandant Schœlsing, is the burial place for many well-known persons including American silent film star Pearl White, the star from, The Perils of Pauline, a favorite of my mother's, and as mentioned the painters Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot, and composer Claude Debussy. I love a good cemetery. I see Pauline in mind's eye having a conversation with Debussy; maybe, she is flirting with him. I digress.

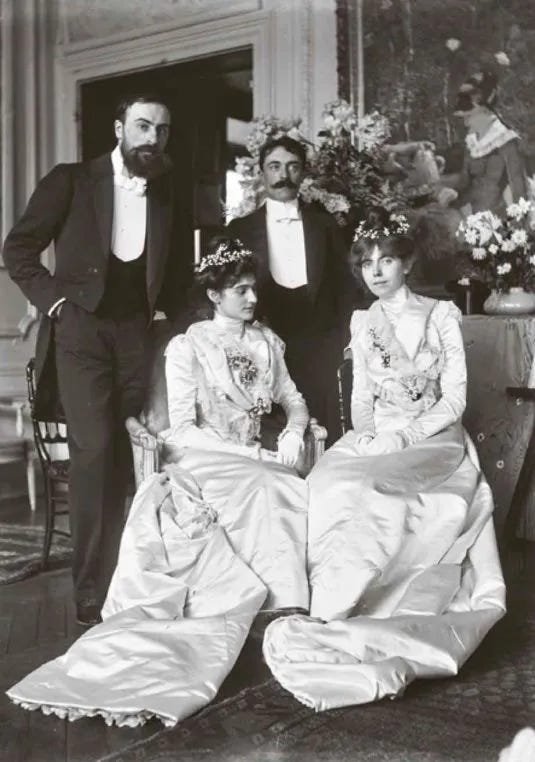

As the week unfolded, it felt as though they had all colluded and planned that we find them in our neighborhood and everywhere we went all week long. I dismissed all this at first but when we walked into the Marmottan Muse with its wall of black and white photos of Berthe Morisot, her daughter, Julie, and the artist and collector, Ernst Rouart, Julie's husband, it seemed that they had met us at the door.

Ernest Rouart, Julie Manet, Paul Valéry and Jeannie Gobillard, rue de Villejust, on their wedding day, 31 May 1900 | Source: Archives of the Mesnil, deposited at Musée Marmottan Monet (Oh, to have been in Paris in May, 1900 and watched these devoted cousins marry in kind, to a famous artist/ collector and a famous poet. I would have thrown rice and rose petals.)

Who were all these people? Why is a major body of their art collections doing in the house that cossets a vast number of Monet's works, to include, Impression Sunrise.

Impression Sunrise, Monet, 1872

One of the key questions is what does Michel Monet, Claude Monet's younger son have to do with this 19th century residence?

Le jardin de Monet à Vétheuil, with Michel Monet and Jean-Pierre Hoschedé. Oil on canvas, Claude Monet, 1880. National Gallery of Art, Washington

It is more than likely that Jean-Pierre was Michel's half brother, the son of Claude Monet ad Alice Hoschides. They served together, these boys, fighting for France during WWI, fighting at the Somme. Michel inherited everything upon his father's death in 1926, Giverny, which was tended by his step-sister until 1947 and all of his father's paintings and his fortune. He died at the age of 66 in a race car accident, leaving everything to the Marmottan Museum.

There is the most exquisite story that links the two families together. During WWI, when Michel, Jean-Pierre and Julie Morisot's husband, Ernst Rouart, were fighting for France. Julie visited Claude Monet at Giverny. She had know him all of her life. He was one of her godfathers, along with Degas and Renoir. Monet was always available to Julie, she sat in the garden and talked to him as he painted one of the many Waterlily compositions.

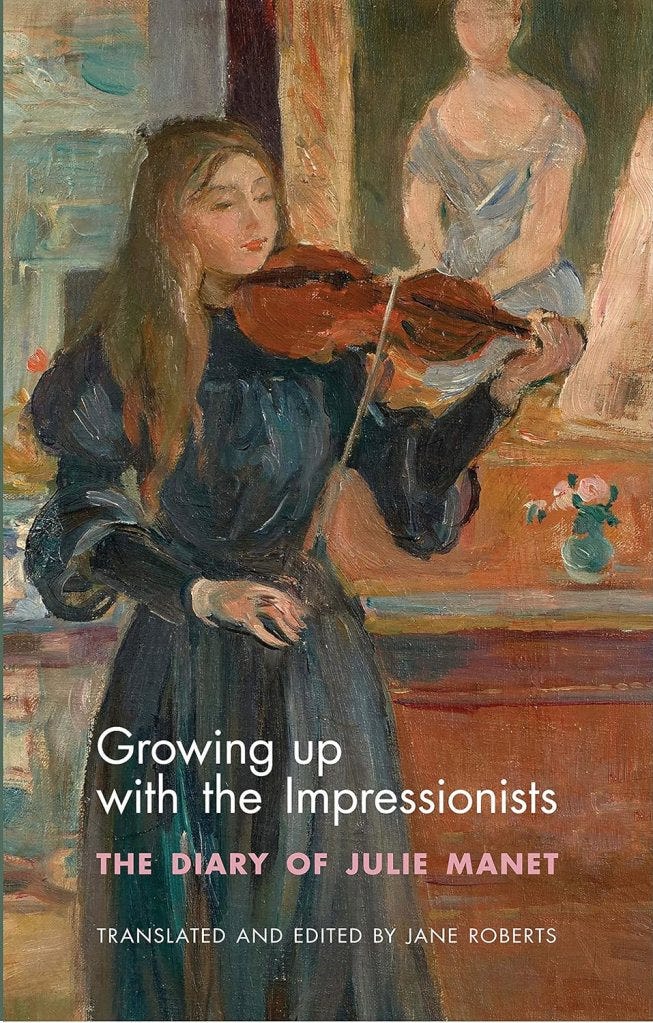

"Some 40 years later, in 1957, Julie Manet, almost 80 and long widowed, went to a Paris gallery to purchase a final painting, one of those she had watched Monet painting. The circle was completed. From birth until her death at the age of 88, Julie was, as she defined herself, “the last Manet” and the embodiment of impressionism." In 1957, she bought the painting from the estate of Claude Monet and ultimately gave it to the Louvre.

What would I give to have heard that conversation between Monet and Julie in about 1915, when the lives of their loved ones were hanging in the balance?

Some of these questions are answered in her diary. She led a very cloistered life within the circle of the artists who changed the face of modern art whilst defining a La Boheme lifestyle. Julie was their precious, cosseted darling, blessed with a sweet, even nature that I attribute to her father, the brother of Edouard Manet.

Berthe Morisot was the first woman Impressionist, the only female represented at the movement's inaugural exhibition in 1874. As a young woman of a certain class, she could not frequent cafés where her fellow artists had met in a lifetime of endless conversation. Instead, like her mother before her, she held a weekly salon at her home in Passy, in Paris's 16th district. Her daughter would grow surrounded by great artists: her mother, her uncle, Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet and Pierre Auguste Renoir, as well as the poet, Mallarme, and the author, Emile Zola.

Mallarme enjoying his second passion

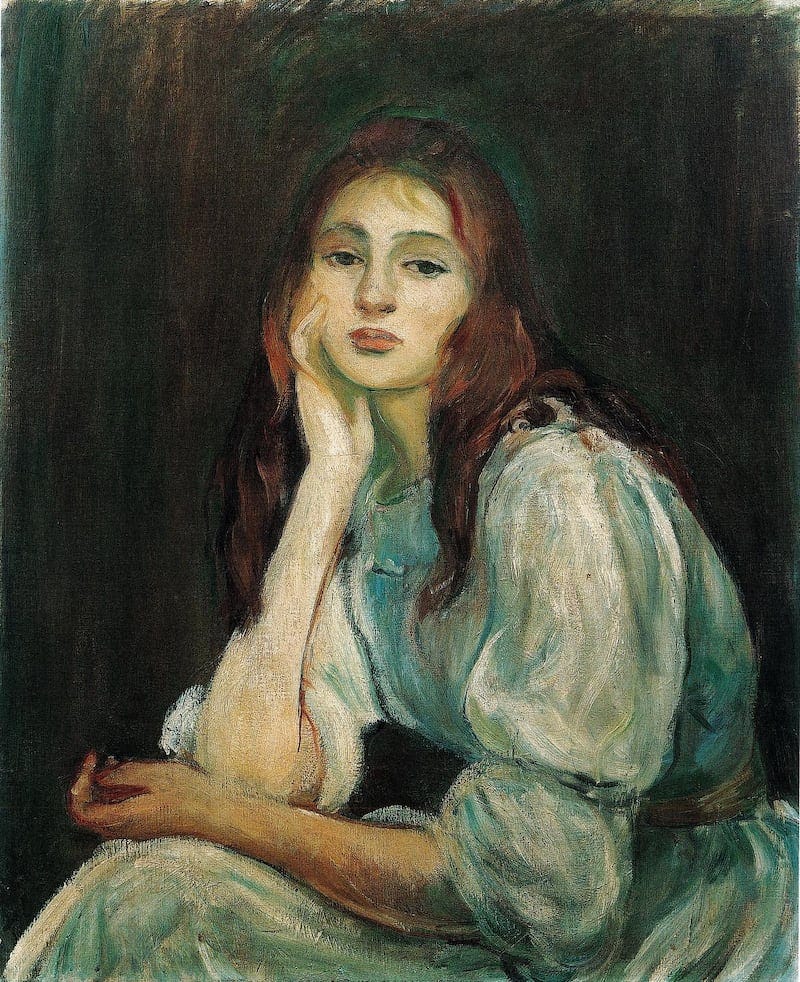

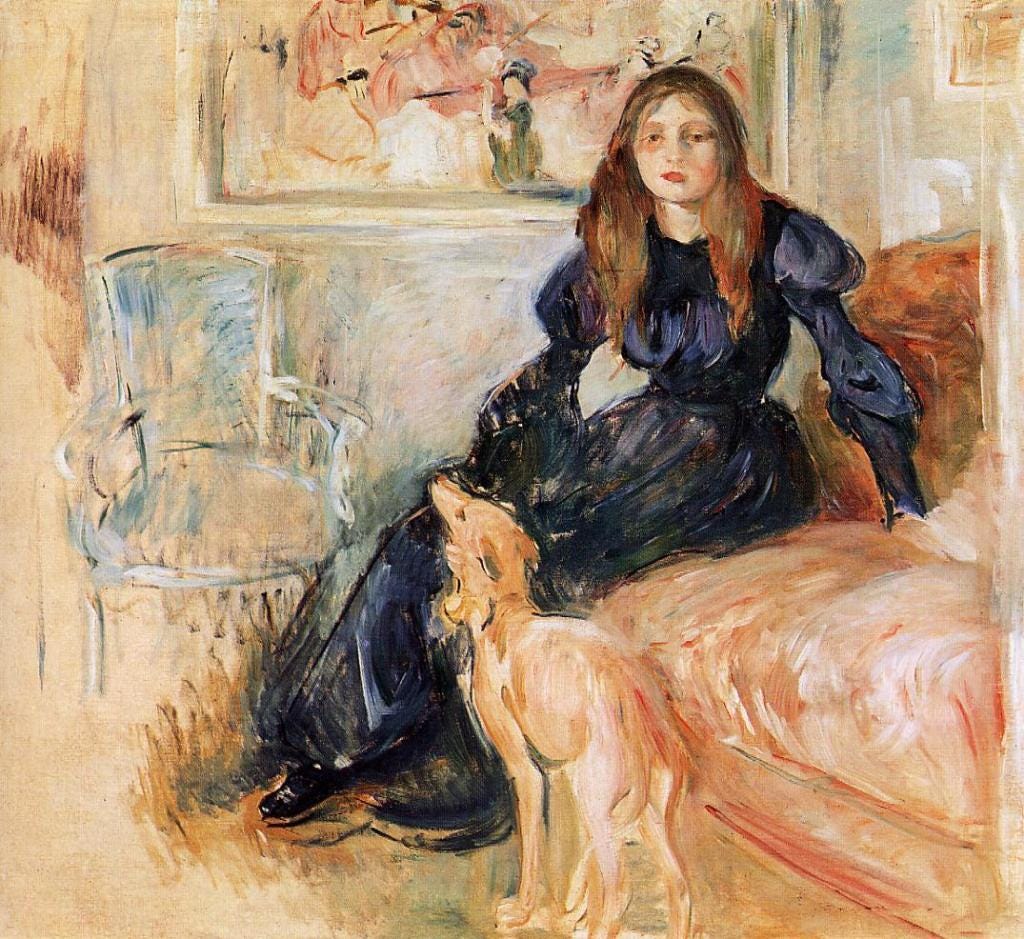

When Julie’s father died in 1892, Mallarmé, a her English tutor, gave the girl a pet greyhound called Laertes, after Hamlet’s loyal friend. Morisot painted her daughter in mourning black, her eyes ringed by grief, with Laertes standing watch beside her.

Mallarmé became Julie’s guardian when she was orphaned three years later. “He gave her a poem and a book every New Year’s Eve,” says George Mathieu, the abstract painter and personal. “... in a family where art is considered the most valuable possession, a sonnet scribbled on a calling card is priceless.”

Julie and the Greyhound, Laertes, Morisot, 1894

When Berthe Morisot died, Julie, at age, 16, continued to live with her cousins, Paule, ten years older and Jennie her senior by two years, the children of Yves, Berthe's older sister. The girls were orphaned but Paule, at age 26, kept the household for the three young women. As mentioned, he girls were tutored by Mallarme, as one of the principle godfathers and a constant source of discussion for the life long friends of the family, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who were attentive and present to give advice to their much loved, very wealthy charges, especially Julie.

Berthe had not married till she was 33. Her husband, Eugene had waited for her, in the years when her work was the center of her life. He was Edouard Manet's shadow brother, always willing to be a model in one of his paintings, always present but a only a glimmer in the blinding light of his brother's charisma and talent. Berthe and Edouard would become very close as colleagues, dear friends, allies in the turbulent years of the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. They had witnessed the destruction and subsequent starvation of their city and shared the news that the entire lifetime of their friend, Pissarro's work had been destroyed and worried that it could happen to them. Manet and his brother would fight in the War and write about eating rats and zoo animals during the occupation. Berthe and her parents stayed in Passy throughout the eight months of siege and occupation, only leaving Paris during the brief but violet Commune. Berthe returned to Paris to find her childhood home windowless from the cannon fire. Her paintings and studio were untouched.

Berthe would pose for Edouard 15 times over the course of their relationship between 1868 to 1874, revealing a a level of intimacy that surpasses any of his many liaisons. I think she was the love of his life. He trusted and esteemed her above all others, the center of a true friendship. She adored him on many levels, there was an undeniable chemistry between them but as a married man with a reputation and her Haute Bourgeoisie background, they were limited in their options. In the shadows stood Manet's brother, Eugene, who understood his brother very well and learned to love and care for Berthe and understand that her art would always be her heart stone obsession. He not only accepted that reality but spent the rest of his life creating an environment for her to further her talent. She married Eugene Manet, the shadow brother, and found a deep seeded happiness with a man who understood her need to paint and her need for a peaceful domestic life. When Julie was born, both Eugene and Berthe wrapped their world around her. She was the center of their lives and the binding topic throughout their marriage. Julie became the child of all the Impressionists, including the radiant Eduoard Manet. Berthe would share his name but find a tranquility in her married life that allowed her to produce some of her finest work and raise her beautiful daughter.

Julie Manet sitting on a Watering Can, Edouard Manet, 1882

The day before Berthe died she wrote to her girl, “My little Julie, I love you as I die; I will love you when I’m dead… you haven’t made me sad once in your little life. You have beauty and wealth; use them well.”

Berthe Morisot, The Artist’s Daughter with a Parakeet, French, 1841 – 1895, 1890, oil on canvas, Chester Dale Collection (Public Domain)

This is a no nonsense farewell from her mother...expressing her undying love and some good advice...use that fortune well. Julie did just that.

A thought that haunts me is where did Julie live and how did she live during WWI and WWII? What happened to this vast collection of art during those unspeakable years is yet to be found by this author? These questions remain unanswered. When I find out, I will share it with you first.

In the meantime, the great repository of the works of the Impressionists is secured in the Musée Marmottan Monet (English: Marmottan Museum of Monet) a private home turned sanctuary, dedicated primarily to the artist Claude Monet but the collection features over three hundred Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, the gifts of Michel Monet and the now, the Manet-Rouart family.

The Marmotton was the hunting lodge of Ernst Marmottan, an industrialist. This neighborhood dates from the 12th century. During the Haussmanian reconstruction of Paris under Napoleon III, the hunting lodge was transformed into an urban villa on the edge of Monceau Park. What a chic Parisian address! Ernst left his fortune and the house to his son, Paul, who was a collector and bibliophile. He turned the house into a reliquary of Napoleonic tidbits complementing the tres chic 2nd Empire aesthetic, to include Napoleon I's short little bed. The house is a journey into the past itself. But once downstairs in the galleries, the world of old friends awaits. We were here many years ago and many years before that. This third trip left us breathless.

Paul Marmottan left his estate to the Academie des Beaux-Arts in the late 1800's. He had no heirs. The museum was opened in 1895.

Michel Monet, without heirs, died in a car crash in nearby Vernon on 3 February 1966, at the age of 87, a month before his 88th birthday. He had bequeathed the estate to the Académie des beaux-arts. He left to the Musée Marmottan Monet his own collection of his father's work, thus creating the world's largest collection of Monet paintings. Here is the reason this is of vast importance:

Monet, Pere, had his own, private collection of the paintings and drawings by masters and friends. He had collected Eugène Delacroix, Eugène Boudin, Johan Barthold Jongkind, Gustave Caillebotte, Renoir, and Morisot.

Above all, Michel inherited his father’s late works. Most of these were part of an ensemble of monumental canvases of water lilies. Between 1914 and 1926, Claude Monet painted 125 large panels, a selection of which he donated to France, which was, in part, a decision made based on the encouragement of his long-time relationship with Clemenceau.

The initial gesture of leaving the Water Lilies to France was rejected by the French government in 1918 due to complications about how Monet wanted them presented. "As a result, Monet refused to let this gift be revealed during his lifetime and what we now know as the Water Lilies of the Orangerie were not seen by the public until 1927. The exhibition caused a scandal; Monet’s last work then went into art historical purgatory. Michel, who owned the largest part of what remained from this great ensemble, found he was the owner of an inheritance that was denigrated. His efforts to rehabilitate the big Water Lilies had little impact in France, and the national museums bought none of the works he put on the market. This is one of the reasons why he decided against bequeathing his collection to the state. Instead, the childless Michel made the Musée Marmottan his sole legatee. When he died, in 1966, over a hundred Monets, including a unique ensemble of large-format Water Lilies, were added to the institution’s collection.

Monet, 1925

Since the salons of Paul Marmottan’s townhouse were too small to show works on such a scale, a new room was specially designed under the garden. In 1970, these canvases, most of which had never been shown, were put on display. They form the world’s biggest collection of works by Claude Monet. The home of Paul Marmottan had grown and was now also the home of the father of Impressionism. The museum became known as the Musée Marmottan Monet." And this, dear reader, is the shorten version!

The arrival of canvases by Monet, Berthe Morisot, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, and Armand Guillaumin was duly celebrated. They formed the cornerstone of the Musée Marmottan’s Impressionist collections.

The museum also contains works by Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, Paul Signac, and others. It also houses the Wildenstein Collection of illuminated manuscripts and the Jules and Paul Marmottan collection of Napoleonic era art and furniture. It is a treasure trove.

In 1993, Julie Manet's collection of her mother and uncle's work and her private collection of major works by the Impressionists who filled her youth, were bequeathed to the museum by her children and grandchildren.

"The Manets, Morisots and Rouarts, their friends and cousins, were a cultivated coterie who expressed themselves in paint or in writing, united by marriage, and through more than a hundred works of art." Compliments of ChasingART

I will save the Rouart Family for another day. Suffice it to say, they owned a dynastic collection of Impressionist art in their own right. Julie, as mentioned, would marry the heir apparent, and join their vast collections. Julie spent her life protecting these works.

The Rouart Collection includes the masterpieces that Julie inherited and that hung throughout her parents' former apartment. Her father-in-law, the industrialist Henri Rouart, owned the world's largest art collection, when he died in 1912. Ernest Rouart and Julie spent 40 per cent of their considerable fortune buying his treasures at auction, with the intention of donating them to the Louvre. After Ernest's death, Julie gave his favorite painting, Corot's bucolic Gardens of the Villa d'Este to the Louvre in his memory. Corot had taught Morisot, and Julie kept her mother's copy of the original. Morisot was Camille Corot's only formal pupil, and the early paintings show that she learned her lessons well.

Tivoli. Les jardins de la villa d'Este , Camille Corot, 1843 (not far from TASIS where Dave and I worked in the mid-90's)

Julie was an accomplished amateur painter but stopped showing her own work when she married.

Her paintings of family members, and a host of letters, poems, diaries, and photographs, document the web of relationships that underpinned much of late 19th- and early-20th-century French art and literature all are part of this incredible private collection. The circle was completed. From birth until her death at the age of 88, Julie was, as she defined herself, “the last Manet” and the embodiment of Impressionism.

Allow me to close this entry with

Debussy's Prelude to an Afternoon of a Faun based on a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé’s eclogue, L’Après-midi d’un faune. It premiered in 1894, only months before Berthe's death. "Though the critics were divided in their response to Debussy’s Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune following its premiere on December 22, 1894, by the Société Nationale de Musique in Paris under the direction of Swiss conductor Gustave Doret, the audience’s reaction was unequivocal: the piece was encored." God bless the French.

L’Apres-midi d’un Faune

Eclogue

The Faun

These nymphs, I would perpetuate them.

So bright

Their crimson flesh that hovers there, light

In the air drowsy with dense slumbers.

Did I love a dream?

My doubt, mass of ancient night, ends extreme

In many a subtle branch, that remaining the true

Woods themselves, proves, alas, that I too

Offered myself, alone, as triumph, the false ideal of roses.

Let’s see….

or if those women you note

Reflect your fabulous senses’ desire!

Faun, illusion escapes from the blue eye,

Cold, like a fount of tears, of the most chaste:

But the other, she, all sighs, contrasts you say

Like a breeze of day warm on your fleece?

No! Through the swoon, heavy and motionless

Stifling with heat the cool morning’s struggles

No water, but that which my flute pours, murmurs

To the grove sprinkled with melodies: and the sole breeze

Out of the twin pipes, quick to breathe

Before it scatters the sound in an arid rain,

Is unstirred by any wrinkle of the horizon,

The visible breath, artificial and serene,

Of inspiration returning to heights unseen.

O Sicilian shores of a marshy calm

My vanity plunders vying with the sun,

Silent beneath scintillating flowers, RELATE

‘That I was cutting hollow reeds here tamed

By talent: when, on the green gold of distant

Verdure offering its vine to the fountains,

An animal whiteness undulates to rest:

And as a slow prelude in which the pipes exist

This flight of swans, no, of Naiads cower

Or plunge…’

Inert, all things burn in the tawny hour

Not seeing by what art there fled away together

Too much of hymen desired by one who seeks there

The natural A: then I’ll wake to the primal fever

Erect, alone, beneath the ancient flood, light’s power,

Lily! And the one among you all for artlessness.

Other than this sweet nothing shown by their lip, the kiss

That softly gives assurance of treachery,

My breast, virgin of proof, reveals the mystery

Of the bite from some illustrious tooth planted;

Let that go! Such the arcane chose for confidant,

The great twin reed we play under the azure ceiling,

That turning towards itself the cheek’s quivering,

Dreams, in a long solo, so we might amuse

The beauties round about by false notes that confuse

Between itself and our credulous singing;

And create as far as love can, modulating,

The vanishing, from the common dream of pure flank

Or back followed by my shuttered glances,

Of a sonorous, empty and monotonous line.

Try then, instrument of flights, O malign

Syrinx by the lake where you await me, to flower again!

I, proud of my murmur, intend to speak at length

Of goddesses: and with idolatrous paintings

Remove again from shadow their waists’ bindings:

So that when I’ve sucked the grapes’ brightness

To banish a regret done away with by my pretence,

Laughing, I raise the emptied stem to the summer’s sky

And breathing into those luminous skins, then I,

Desiring drunkenness, gaze through them till evening.

O nymphs, let’s rise again with many memories.

‘My eye, piercing the reeds, speared each immortal

Neck that drowns its burning in the water

With a cry of rage towards the forest sky;

And the splendid bath of hair slipped by

In brightness and shuddering, O jewels!

I rush there: when, at my feet, entwine (bruised

By the languor tasted in their being-two’s evil)

Girls sleeping in each other’s arms’ sole peril:

I seize them without untangling them and run

To this bank of roses wasting in the sun

All perfume, hated by the frivolous shade

Where our frolic should be like a vanished day.’

I adore you, wrath of virgins, O shy

Delight of the nude sacred burden that glides

Away to flee my fiery lip, drinking

The secret terrors of the flesh like quivering

Lightning: from the feet of the heartless one

To the heart of the timid, in a moment abandoned

By innocence wet with wild tears or less sad vapours.

‘Happy at conquering these treacherous fears

My crime’s to have parted the dishevelled tangle

Of kisses that the gods kept so well mingled:

For I’d scarcely begun to hide an ardent laugh

In one girl’s happy depths (holding back

With only a finger, so that her feathery candour

Might be tinted by the passion of her burning sister,

The little one, naïve and not even blushing)

Than from my arms, undone by vague dying,

This prey, forever ungrateful, frees itself and is gone,

Not pitying the sob with which I was still drunk.’

No matter! Others will lead me towards happiness

By the horns on my brow knotted with many a tress:

You know, my passion, how ripe and purple already

Every pomegranate bursts, murmuring with the bees:

And our blood, enamoured of what will seize it,

Flows for all the eternal swarm of desire yet.

At the hour when this wood with gold and ashes heaves

A feast’s excited among the extinguished leaves:

Etna! It’s on your slopes, visited by Venus

Setting in your lava her heels so artless,

When a sad slumber thunders where the flame burns low.

I hold the queen!

O certain punishment…

No, but the soul

Void of words, and this heavy body,

Succumb to noon’s proud silence slowly:

With no more ado, forgetting blasphemy, I

Must sleep, lying on the thirsty sand, and as I

Love, open my mouth to wine’s true constellation!

Farewell to you, both: I go to see the shadow you have become.

We are going to Paris in April and will add the Marmottan to our must see list. Thank you!